Executive Orders, Emergency Orders, and Legislative Orders: A Uniquely Complex Planning Environment

In a recent report on power system reliability risk priorities, the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) identified “volatile energy policy” as one of the key attributes of the current energy market environment. Although the NERC report is mainly concerned with the power system, its inclusion of abrupt and accelerating changes in policy as a current risk has a broader resonance. The Trump Administration has issued more than 200 actions that are reshaping U.S. energy markets. This wholesale reworking of energy policy requires that decision-makers fully comprehend not simply the details of each individual Executive Branch and legislative action, but also how these initiatives interact. The interactions are complex and not always obvious, posing an exceptional challenge to public and private entities.

The oil and gas production sector provides such a case. The Administration has been aggressively promoting additional output through tax incentives and other regulatory initiatives, but at the same time tariff policy may increase drilling costs, making it more costly to increase production, and also inhibit exports to some markets. For example, China has imposed a retaliatory 15% tariff on liquified natural gas (LNG) imports from the United States. What the net effect of these factors will be on exports, domestic gas supply, and natural gas prices is a complex question without an obvious answer (further discussed below). Another case where the long-term impacts of recent policy changes are unclear is, perhaps surprisingly, electric vehicles (EVs). On his first day in office, Trump signed executive orders targeting national vehicle pollution standards and California’s Clean Air Act waiver. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) eliminated tax credits for electric EVs and will almost certainly reduce EV sales in the immediate future. However, by selling more conventional cars, which have bigger profit margins, there is an argument that over the long-term the auto manufacturers will have more funds to invest in R&D and new factories, ultimately benefiting advanced technologies and in particular EVs.

Electric power generation and fuel supply provide another good illustration of the complexity of policy interactions. The Trump Administration has been highly supportive of coal as a power source, which it describes as “critical to meeting the rise in electricity demand.” In support of this policy the Administration has, for example, directed a two-year delay in the enforcement of the Mercury and Air Toxics Standards rule for several coal-burning power plants; is seeking to roll-back the endangerment finding for greenhouse gases, the foundation of climate regulation that largely targets coal combustion; and has sought to maintain the reliability of the power grid by using emergency orders to delay the retirements of coal-fired power plants. But as noted above, the Administration and Congress are also promoting expanded production of natural gas. Natural gas has long-since surpassed coal as the largest source of power generation in the United States because of inherent economic advantages in production, transportation, and generating technology. If the Administration’s policies increase the supply of low-cost natural gas, a knock-on effect may be to make it even more difficult for coal plants to compete with gas generation in the dispatch order, much less warrant the construction of new coal plants (see the coal post in the OnLocation blog series on the Annual Energy Outlook (AEO) 2025). As discussed in an earlier blog, merely delaying retirements will not be enough to revive the coal industry; consequently, the Administration may need to pursue even more aggressive policies to achieve its goal of sustaining coal-fired generation.

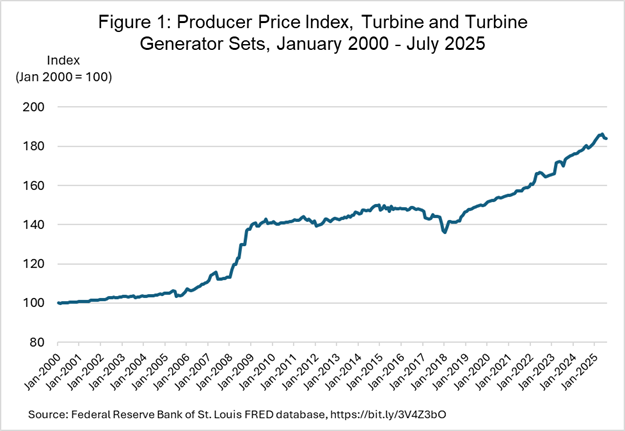

However, gas-fired power is subject to the same kind of policy crosswinds as the coal sector. One of the Administration’s objectives is to increase and maximize American exports of LNG. While this policy could have many economic benefits, it may also put pressure on domestic gas supply and prices. For instance, the August 2025 issue of the Energy Information Administration’s Short-Term Energy Outlook notes that “Rising natural gas prices [into 2026] reflect relatively flat natural gas production amid an increase in U.S. liquefied natural gas exports.” Another factor is tariffs, which may exacerbate pre-existing issues with the sourcing and availability of gas-fired generating equipment, especially combustion turbines. Tariffs may also contribute to the already increasing cost of building new gas-fired power plants (see Figure 1). The overall effect of these factors, at least in the short-term, may be to encourage data center developers and utilities that need to rapidly install new generating resources to rely on renewable resources such as solar power. This could be the case although current federal policy is to move away from solar and wind resources.

As the foregoing discussion illustrates, federal energy policy has many moving parts, and understanding their interactions will be critical for decision-makers looking to wisely plan and invest in energy and related markets. Sophisticated integrated models that capture the interactions of the energy market sectors, and feedback with the larger economy, are essential tools in this environment. OnLocation has for decades been a primary developer and operator of the National Energy Modeling System (NEMS), the premier model for energy market projections. Our energy experts are uniquely qualified to help you navigate these complex policy interactions and challenges.