Coal Power: Decline or Stability?

The past 20 years have been unkind to the coal-fired segment of the electric power industry. A wave of retirements and conversions to use natural gas — triggered by the advent of inexpensive gas-fired generation, low-cost renewables, and tightened environmental rules — have reduced the industry to a shadow of its former self. Coal generating capacity has dropped about 45 percent from its peak. The coal share of U.S. total generation peaked at close to 60 percent in the 1980s. In 2024 it was only about 15%. Wind and solar power combined are now a larger source of power than coal, and the gap will only grow in the future.

However, a slowdown in the seemingly irreversible decline of coal-fired generation may now be foreseeable. One factor is the advent of a new fossil-friendly administration in Washington. Another is the surge in electric power demand, largely driven by data centers and artificial intelligence (AI). While there are no plans on the books for major new coal power plants, what may be in offering is a slowdown in the rate of coal generator retirements and conversions to use alternate fuels. In this blog we will look at the current state of planned coal retirements, recent delays in planned retirements, and the consequences for coal generation and coal demand.

Plants, Units, and Retirements

At the outset we need to clarify basic terminology. A “power plant” is a site that contains one or more generating units. These units may all use the same fuel or different fuels and technologies. Retirements are in terms of individual generating units, not necessarily for the entire plant at one time. And the term “retirement” itself can have different shades of meaning. If a coal unit is shut down and demolished, that is retirement by any definition. However, there are instances in which coal units are modified to burn natural gas as the sole fuel or co-fired with coal.

When coal is completely displaced, the boiler is adapted to burn 100 percent gas and the coal-handling equipment is decommissioned. An example is the two-unit coal-burning J.K. Spruce plant in Texas. Spruce 1 is scheduled to be completely retired in 2028, but in the same year Spruce 2 will be converted to run exclusively on natural gas. From a coal standpoint, Spruce 2 will be as “retired” as unit 1.

Finally, note that the data reported in this article is for relatively large generating units (minimum capacity of 125 MW) operated by utilities and independent power producers. Smaller units for which there may be data availability issues, and the minor industrial and commercial coal-fired generating sectors are excluded.

Characteristics of Retiring Coal Units

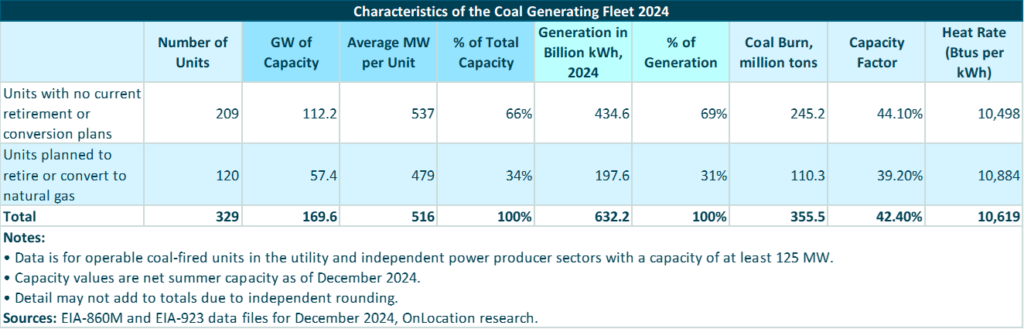

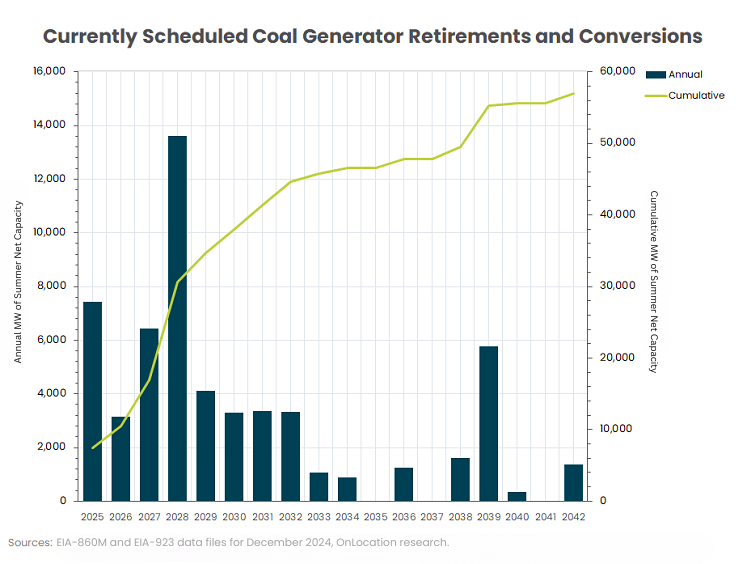

As shown in Table 1, at the end of 2024 the coal generating fleet (using the criteria described above) consisted of 329 generating units with 169.6 gigawatts (GW) of generating capacity. Of this total, about a third, 57.4 GW, are currently scheduled to either retire or undergo conversion to burn exclusively natural gas. Figure 1 illustrates the timing of retirements and conversions.

One observation is that, at least in broad brush, the units scheduled for retirement and all others have similar operating characteristics. As shown in Table 1, the non-retiring units are somewhat larger with slightly higher capacity factors and lower heat rates (i.e., more efficient) than those planned for retirement or conversion. The differences are clear but not dramatic and suggest that other factors, such as local demand forecasts and environmental control issues, play a major role in retirement decisions.

Delayed Retirements

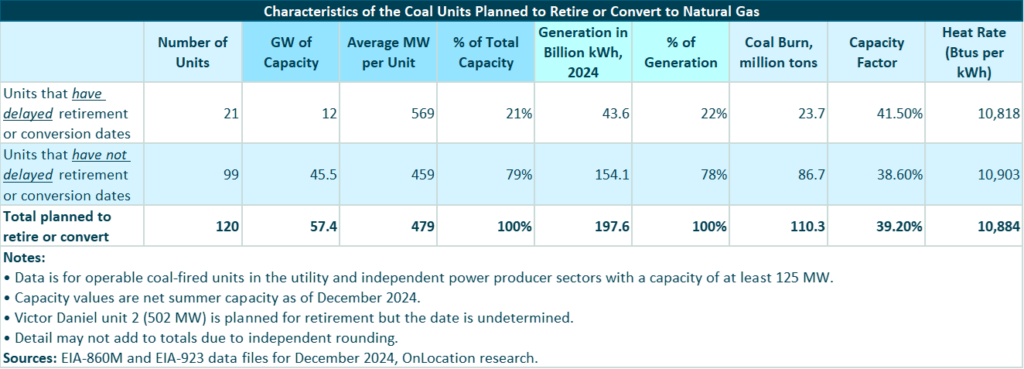

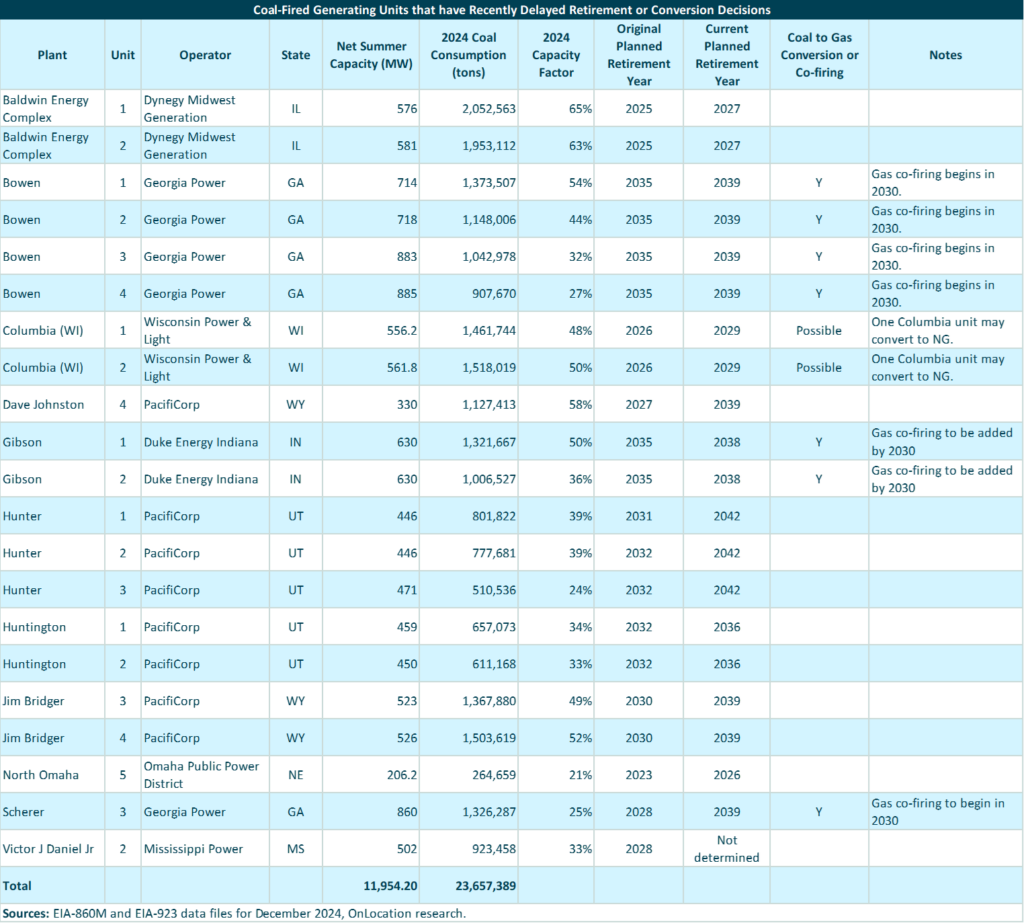

More coal retirement and conversion announcements will certainly be forthcoming, but there may also be decisions to delay these plans. For this blog we identified 22 coal units for which retirements and conversions have been recently delayed, listed in the Appendix table at the end of this article. As shown in Table 2, these delayed units total 12 GW or 21 percent of the 57.4 GW of coal generators currently planned for retirement or conversion.

The table also illustrates the differences between the units that have and have not delayed retirements and conversions. The delaying units have better capacity factors and heat rates and are larger on average by about 110 MW. Looking at the totality of the data (Tables 1 and 2), the unsurprising pattern is that larger units with higher utilization and lower heat rates are more likely to continue to operate as coal units or, if planned for retirement or conversion, to win a reprieve in the form of a delay to the shut-down date.

With respect to the units that have delayed retirement or conversion, the following examples illustrate the diversity of factors that are part of the delay decision:

- A straightforward case is North Omaha unit 5 in Nebraska. The unit was scheduled to close in 2023, but due to increased demand from data centers, the retirement date has shifted to 2026 and may be delayed further.

- More complex is the situation at Jim Bridger units 3 and 4 in Wyoming. The original plan was to convert the units to burn natural gas prior to final retirement in 2037. The new plan is to add carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) equipment to the units by 2030 and continue operation as coal burners until retirement in 2039.

- Increased demand, including from data centers, has led Southern Company to delay the retirement of coal units at Plants Bowen and Scherer in Georgia and Victor Daniel in Mississippi. Bowen 1-4 had planned to retire by 2035 and Scherer 3 in 2028. Now all five units will begin co-firing natural gas by 2030 and stay in operation until 2039. Victor Daniel unit 2, also originally planned to retire in 2028, currently has no fixed retirement date, although it appears that retirement is still the intent.

- Hunter units 1-3 in Utah were originally scheduled to retire in 2031 and 2032. Following favorable rulings on environmental compliance, their retirement dates have been extended to 2042.

These examples illustrate the uncertainties and variables associated with retirement and conversion delays. The retirement date for Hunter is now so far in the future that any number of electricity demand, policy, fuel cost, and technology contingencies could lead to a change. The plan to install CCS equipment at Bridger relies on technology which has been successful at the pilot scale but has never been deployed commercially in the United States. The plans for the North Omaha and Southern Company units are all based on demand forecasts which are just that – projections, not certainties. Higher or lower demand growth could lead to new plans.

The Bigger Picture

One consequence of delayed retirements of coal burning generators is, of course, continued emissions of greenhouse gases from a high carbon fuel and the resulting climate change impacts. But for this blog we will focus on the significance of coal retirements and delays on the electric power and coal production industries.

For coal producers, the continued operation of coal burning generators is a matter of life and death. Demand for coal has dropped from a high of 1,128 million tons in 2007 to an estimated 409 million in 2024, a 64 percent decline. The industry also exported about 108 million tons of coal in 2024, but whether any of this will be at risk due to current tariff and trade issues is yet to be seen.

The coal plants included in this study burned 356 million tons of coal in 2024, or 87 percent of total national consumption (the balance was shared among smaller power plants, industrial and commercial customers, and coke ovens). In round numbers, at current utilization rates every 1,000 MW (1 GW) of coal capacity accounts for about 2 million tons of annual coal demand. Given the reduced state of the coal industry, almost any delay in retirements is a material benefit to coal producers.

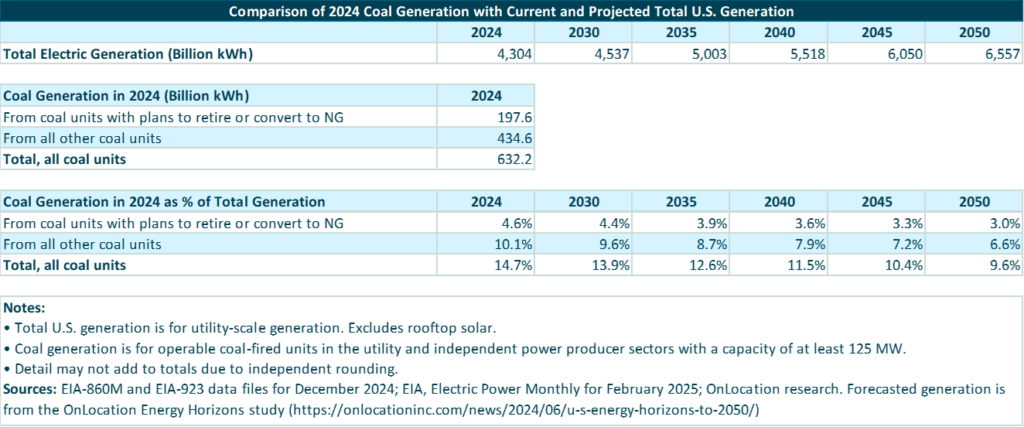

In the case of the electric power industry, as noted earlier, the importance of coal generation has greatly declined and if current trends continue, its importance will continue to shrink. Table 3 shows projected U.S. total electricity generation to 2050 as estimated in OnLocation’s Energy Horizons study (Reference Case). These estimates are compared to coal generation in 2024.

OnLocation is projecting robust growth in U.S. power demand and therefore net generation, increasing 52 percent by 2050. Assuming that only the coal units with current plans to retire or convert to natural gas stop using coal – that is, all other coal-fired units continue to operate indefinitely – the coal share of net generation drops to just 6.6 percent by 2050. Even in the improbable case that every existing coal unit delayed retirement indefinitely, the coal share is a meagre 9.6 percent in 2050.

An argument can be made that coal-fired generation, which can be called on as-needed unlike variable renewables, is more important to power system reliability than its share of total generation might suggest. There is certainly some strength to this argument, but as shown in Table 1, the average capacity factor for coal plants is only around 40 percent. This indicates how the deteriorating economics of coal-fired power have forced coal generators into cycling (intermittent) or even peaking service, which can be met as easily by natural gas-fired plants.

What the foregoing suggests is that if coal is not to fade into near inconsequence as a source of electricity at least two things must happen. First, more generating units have to delay or avoid retirement. Plant operators might follow the example of Pacificorp and consider adding carbon capture equipment to existing plants. Second, the utilization of units will have to increase. Even if the entire existing coal fleet is preserved indefinitely, utilization will have to increase by 50 percent – that is, in lockstep with the increase in total generation – to maintain the coal share of generation at the current 15 percent.

The foregoing assumes that a large-scale domestic buildout of new coal-fired power plants is unlikely. However, the new administration has made clear its support for new coal power development overseas; perhaps it will do the same at home.

Conclusion

While coal’s share of U.S. electricity generation is projected to decline, its future trajectory remains uncertain, influenced by policy direction, electricity demand growth, and carbon management technologies. For example, OnLocation’s recently updated data center report illustrates how increased demand combined with more fossil-friendly federal policies may slow the decline in coal generation, including delayed retirements.

Delayed retirements may extend coal’s operational role in the short term, but long-term sustainability will require either technological breakthroughs—such as large-scale carbon capture—or strategic policy shifts. As energy markets evolve, decision-makers must consider data-driven insights and scenario analysis to adapt to an increasingly dynamic power sector. In this complex and uncertain environment, energy forecasting models such as OnLocation’s implementation of the National Energy Modeling System (OL-NEMS), and the experience and insight of our energy economists, can help policymakers and businesses navigate the future. For further information contact us here.

Appendix Table: Coal-Fired Generating Units that have Recently Delayed Retirement or Conversion Decisions

UPDATE: A version of this blog was included in Power Engineering on April 23, 2025.