Prospects for Fossil-Fired Generation

On January 10, 2025, Constellation Energy, the nation’s largest operator of nuclear power plants, announced its plan to acquire Calpine Corp., the largest operator of gas-fired generation. When completed, the $16.4 billion deal will make Constellation one of the largest power plant operators in the United States. The combined companies will have about 60 GW of capacity, primarily nuclear (21 GW) and natural gas (26 GW). This is clearly a bet on clean (or at least relatively clean) electricity, but also on the continued viability of fossil fuels in the era of climate change.

In this blog, we will explore the prospects for maintaining a significant fossil fuel presence in the domestic electric generation market. Government policy changes can bend the industry’s trajectory to some degree, but economic factors – especially demand growth and the relative costs of generation alternatives — will remain the main drivers.

The estimates and insights presented below are based on OnLocation’s ongoing analyses of U.S. energy economics and in particular two recent studies: one is our assessment of data center demand, and the other is our Energy Horizons long-term forecast to 2050. Both studies are based on a customized version of the National Energy Modeling System (OL24-NEMS), for decades the preeminent system for projecting the U.S. energy economy.

Coal Faces the Harder Road

Of the two major fossil fuels, coal and natural gas, it is coal that faces the greatest challenges. Steam electric coal generation, independent of its climate impacts, has found it difficult to compete with modern natural gas combined cycle (NGCC) plants. However, the recent surge in power demand has led to delays in the planned retirement dates for some coal units and if the new administration in Washington rolls back recent EPA rules, more retirements may be postponed. Nonetheless, coal still faces an uphill battle due to competition from lower cost and more climate friendly natural gas, solar, and wind technologies. The Energy Information Administration (EIA) database that tracks planned power plants currently contains no new coal units and most existing units are 25 or more years old. Coal plants with carbon capture could be a lifeline for the coal industry, but our Energy Horizons analysis shows that this technology would need additional tax credits or other incentives to overcome the significant cost of carbon capture as well as siting, permitting and building, CO2 pipelines and storage sites to transport and permanently store the captured CO2.

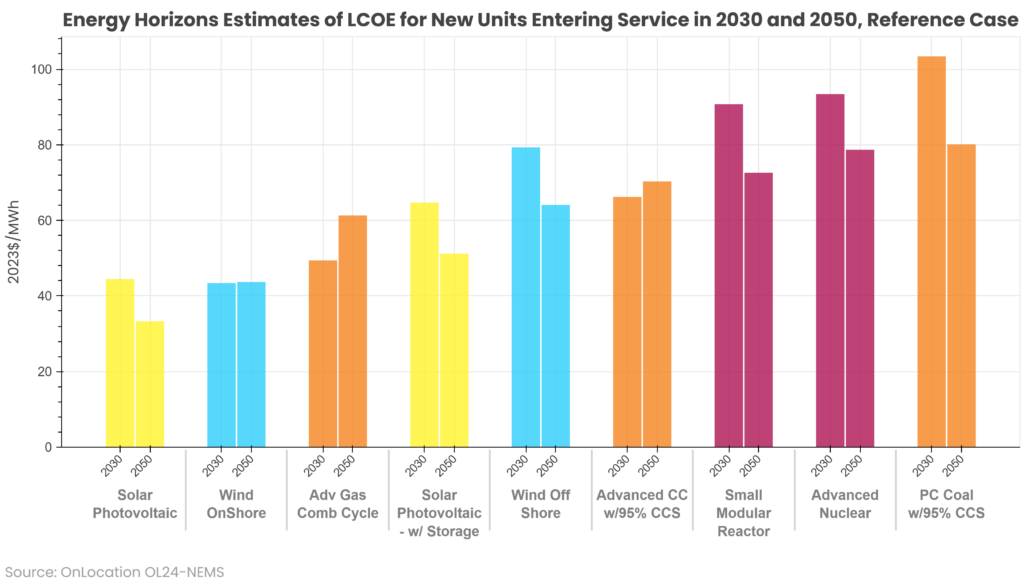

The fundamental issue is cost. Figure 1 displays the Energy Horizon estimates of the levelized cost of electricity (LCOE ) – that is, the average cost of electricity from a generation source over the lifetime of a power plant, providing a rough view of relative economic attractiveness — for new generating units entering service in 2030 and 2050 (important to note that these projected estimates take into account renewable energy tax credits, incentives, and policies as of 2024). Coal with carbon capture is the highest cost option in both periods, and these estimates do not include the ancillary infrastructure, such as a pipeline network and sequestration facilities, needed to transport and store captured CO2. In sum, it is hard to envision the remaining coal generation as anything other than an industry facing great challenges. But the prospects may be better for gas-fired power.

Rapid Demand Growth

The potential savior for fossil generators is the growth in power demand and the characteristics of that demand. For decades growth in U.S. electricity demand has been minimal. For the period 2000 – 2023, growth in electricity sales averaged only 0.5% per annum. For six of the 10 years between 2014-2023, electricity demand growth was either zero or negative. But these trends are about to reverse. EIA’s short-term estimate as of January 2025 is that electricity sales increased by 2.2% in 2024 and will grow another 2.1% in 2025. OnLocation’s Energy Horizons study forecasts that this will kick-off robust electricity sales growth continuing to mid-century. Growth is expected to average 1.7% annually (2025-2050). This rate might not seem that high, but by 2050 the change is dramatic, with total sales more than 50% higher than in 2025 (from 3,956 to 6,059 billion kWh). A large chunk of the demand growth is expected to come from data centers, turbocharged by AI computing. In our recent data center study, OnLocation estimated that data center demand will increase from about 169 TWh in 2024 to a range of approximately 600 to 800 TWh by 2050, accounting for more than 10 percent of total U.S. electricity demand. These facilities require firm power, 24/7. Another consideration is anticipated increases in peak demand as total sales climb. As part of the justification for its Calpine deal, Constellation explicitly cited projected increases in peak load in ERCOT and PJM by 2035. Meeting peak demand requires reliable and dispatchable power.

The Price of Power

But what kind of generation will be used to meet this demand? The main thrust of the energy market, in the Unites States and abroad, seems to be heading in the direction of an increasingly solar future. The Economist, a journal not given to hyperbole, in a recent special report on the global adoption of solar power, described it as nothing less than “revolutionary” in the history of energy and industrial development. The Economist found, crucially, that solar PV is becoming so inexpensive that the expansion of the solar market is no longer entirely dependent on climate policy: it can often stand on its own as an option for new capacity.

Nonetheless, there may be a continuing window for gas-fired generation to meet the need for firm and dispatchable energy. As noted above, Figure 1 displays the Energy Horizons estimates of the LCOE for new units constructed in 2030 and 2050. These estimates need to be viewed with appropriate caveats. They represent national averages, but costs can vary with location; they assume a fixed capacity factor rather than utilization rates that can vary; and it is hard to make a simple comparison between technologies with different operating profiles, such as a nuclear plant and a variable output wind farm. Nonetheless, they are indicative of the cost relationships that help determine capacity growth and generation forecasts.

As shown in the figure, in 2030 solar PV and onshore wind power are the least expensive technologies. But these variable-output technologies cannot provide firm power, and at least for the time being the lowest cost dispatchable option is the NGCC without carbon capture. By 2050, Energy Horizons projects that solar PV with battery storage, another firm technology, will be less expensive than the gas-fired combined cycle, but this still suggests that there will be an interval over the next quarter century when the NGCC will remain a viable option for new construction. Units that exist today that have already recovered a portion of their investment costs will be even more competitive.

Natural gas plants have lower emissions than coal power but still emit CO2. For operators seeking a zero-carbon option, natural gas with carbon capture currently appears to be a less likely path for generators to follow than renewables or possibly nuclear power. In particular, and as discussed in a recent OnLocation blog post, data center operators have shown a clear taste for nuclear power as the zero carbon energy source of choice. The NGCC with carbon capture notionally has an LCOE advantage, but as discussed above, a plant with carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) is viable only as part of a system that includes a means of transporting and storing the captured CO2. From a zero-carbon standpoint, a nuclear plant is more of a stand-alone option that does not require the construction of new regional or national-scale energy infrastructure, although nuclear power has its own challenges including the continuing need for a permanent nuclear waste repository. Also, the small modular reactor (SMR) technology that has attracted the attention of data center operators has yet to be licensed to operate in the U.S.

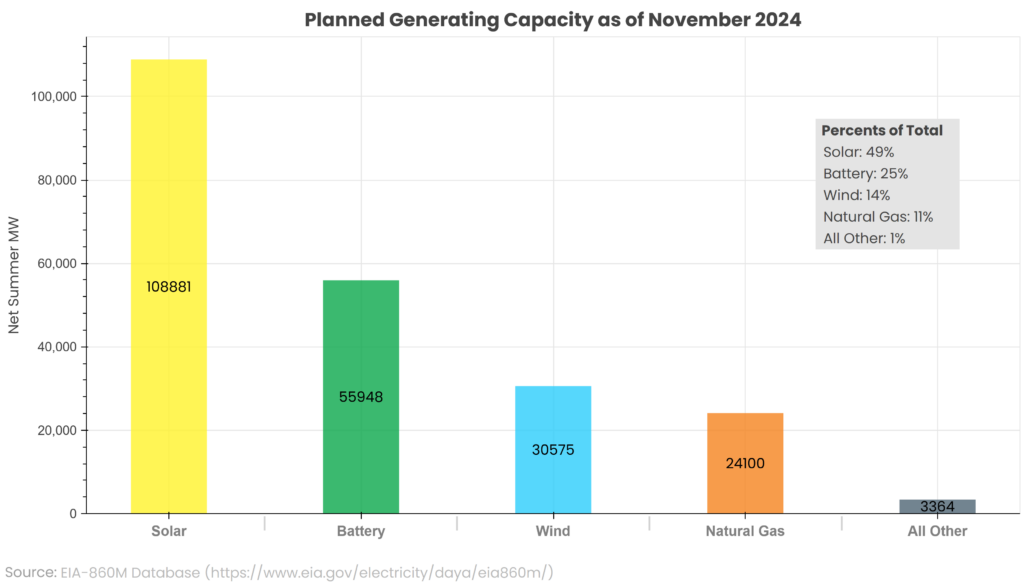

None of this should be interpreted as suggesting a boom is likely in natural gas generation. Figure 2 summarizes the EIA’s inventory of planned generating capacity as of late 2024. Consistent with the cost advantage of solar and wind power discussed above, renewables (including battery storage) dominate planned capacity. But planned natural gas combined cycles and peaking turbines are not immaterial (24 GW) and illustrate the point that there may still be a role for new fossil capacity.

An Uncertain Future

The precise course of events is, naturally, contingent on future developments which are unpredictable, not the least of which are the policies of the incoming Trump Administration and its successors, in particular regarding renewable energy incentives and permitting. Grid-scale battery prices may drop much faster than expected, or the federal government might choose to bite the bullet and spend billions of dollars in incentives to create a national CCS network that could help revive coal-fired generation and further expand the market for gas-fired power. Or a hydrogen energy economy may make it possible to transition gas-fired combined cycles to a zero-carbon fuel. In a market facing the potential of such extraordinary change and uncertainty, energy forecasting models such as OL24-NEMS, and the experience and insight of our energy economists, can help policymakers and businesses navigate the future. For further information contact us here.